Back to school with UCLA’s Food Studies program

Read the original post by Evan Kleiman | Photo Courtesy of Jack Bobo | August 22, 2025

Although he leads Food Studies at UCLA, Jack Bobo also has an entry in Wookieepedia.

Yes, food studies at the university level is a thing — as it should be. All the joys and ills of human life — health, the environment, social equity — are a venn diagram with food.

Jack Bobo, the Executive Director of the UCLA Rothman Family Institute for Food Studies, has an impressive resume. He was the Director of Global Food and Water Policy at The Nature Conservancy and a senior advisor on global food policy at the U.S. Department of State. And, because you never know where life will take you, he has an official entry in Wookieepedia.

A friend of his from junior high who earned a PhD in paleontology got a call, one day, from Lucasfilm to help them track down locations in Tunisia. So he ended up working for Lucasfilm and writing several best-selling Star Wars books. “One night, he called me up and said, ‘I need to do a spread on lightsaber combat. I know you’re a fencer. Can you help me?'” Jack says. “So we spent a weekend designing the different forms of lightsaber combat for George Lucas.”

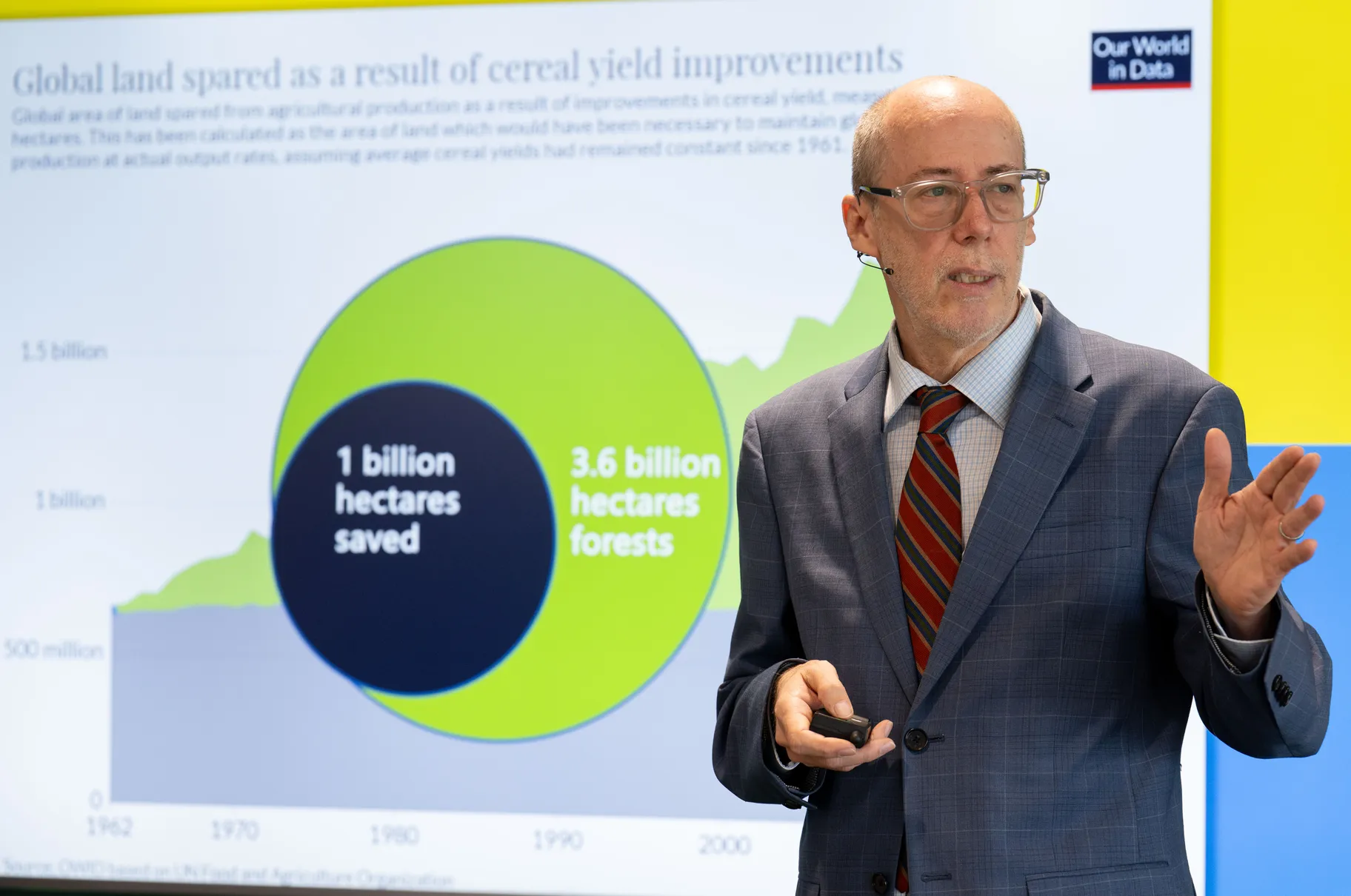

“In many ways, there’s nothing that has a bigger, more negative impact on the planet than agriculture,” says Jack Bobo.

So what is Food Studies and why does it matter? “It’s really broad, and it really touches on our entire food system,” he says.

UCLA offers a Food Studies minor and the law school is home to the Resnick Center for Food Law and Policy. There’s the Healthy Campus Initiative, which aims to prioritize the health and wellness of students, staff, and faculty. So across the institution, there are several initiatives and programs that touch on food. The goal of the Rothman Family Institute is to bring them together.

“We’re trying to figure out, how do we have the biggest impact with what we’re doing? How do we identify the challenges, both at the societal level and the planetary level, as well as the individual level? In many ways, there’s nothing that has a bigger, more negative impact on the planet than agriculture yet there’s also just nothing more critical for our daily survival,” Jack says.

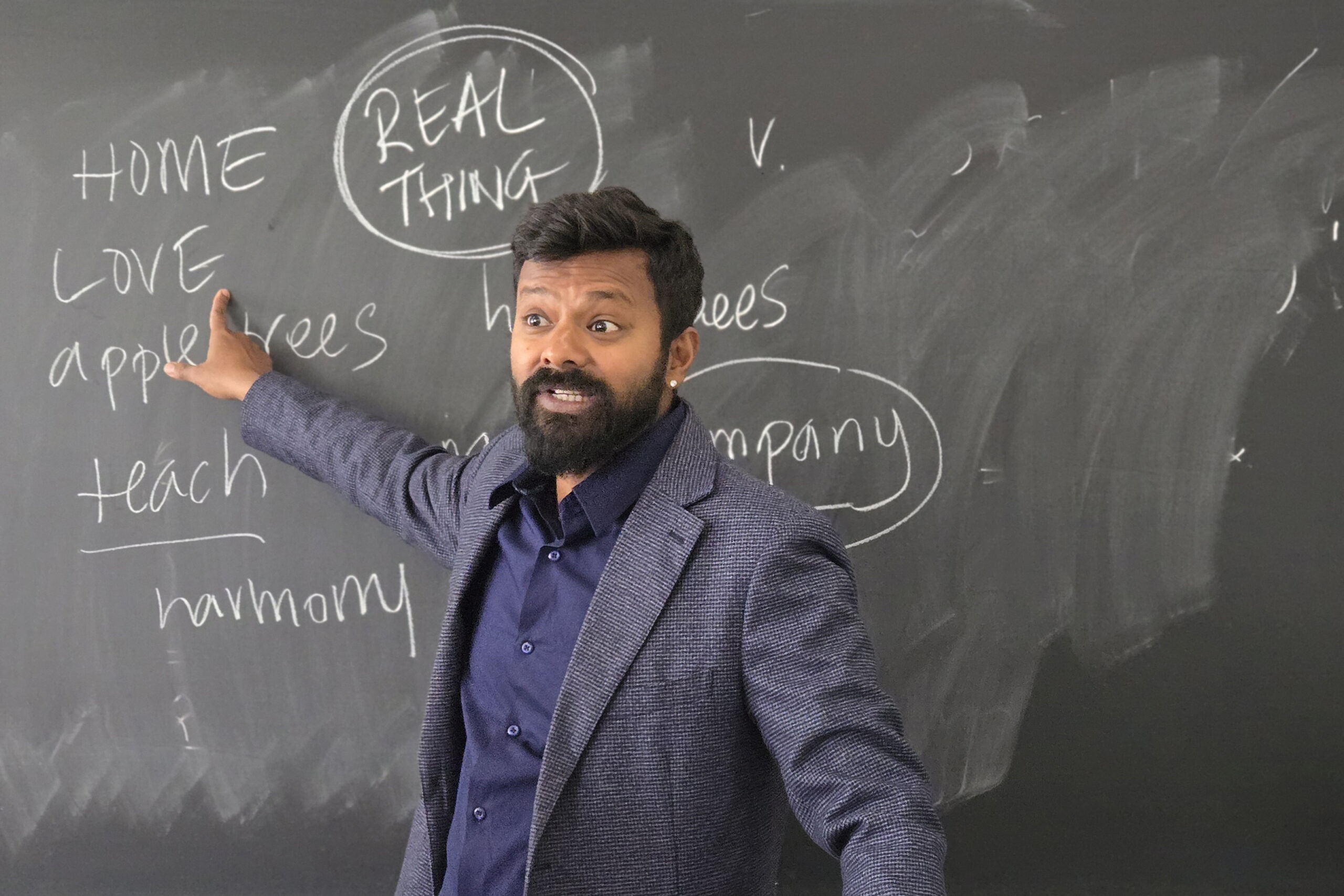

In his role overseeing food studies at UCLA, Jack Bobo aims to connect many disparate programs and initiatives.

And what is his role in UCLA’s Food Studies program?

“There are a few things that we’re trying to do. The first is we want to connect all the research that touches on food and agriculture at UCLA already. If we can connect that research, hopefully we can do a better job of all the things we’re already doing. That’s the internal part of it,” Jack says.

Externally, he serves as an ambassador for that research, bringing that research to the world. “How do we talk about problems in a way that actually brings people together to find solutions, instead of further polarizing society?” he muses. “I’m really interested in how we change the nature of dialogue so that people are excited to work together instead of working against each other.”