The annual award honors a mid-career faculty member with a distinguished record of teaching, research and service

Read the original post by Wendy Soderburg | Photos by Osvadlo Tarula | September 15, 2025

When Amy Rowat — a UCLA professor in the department of integrative biology & physiology — was a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard University back in 2010, she was presented with a unique opportunity. One of her fellow postdoc colleagues had invited famed Catalan chef Ferran Adrià — widely known as a pioneer of modernist cuisine — to visit the campus. Rowat was tapped to participate because she had previously developed public events that engaged general audiences, especially families and children, in scientific concepts using food and cooking.

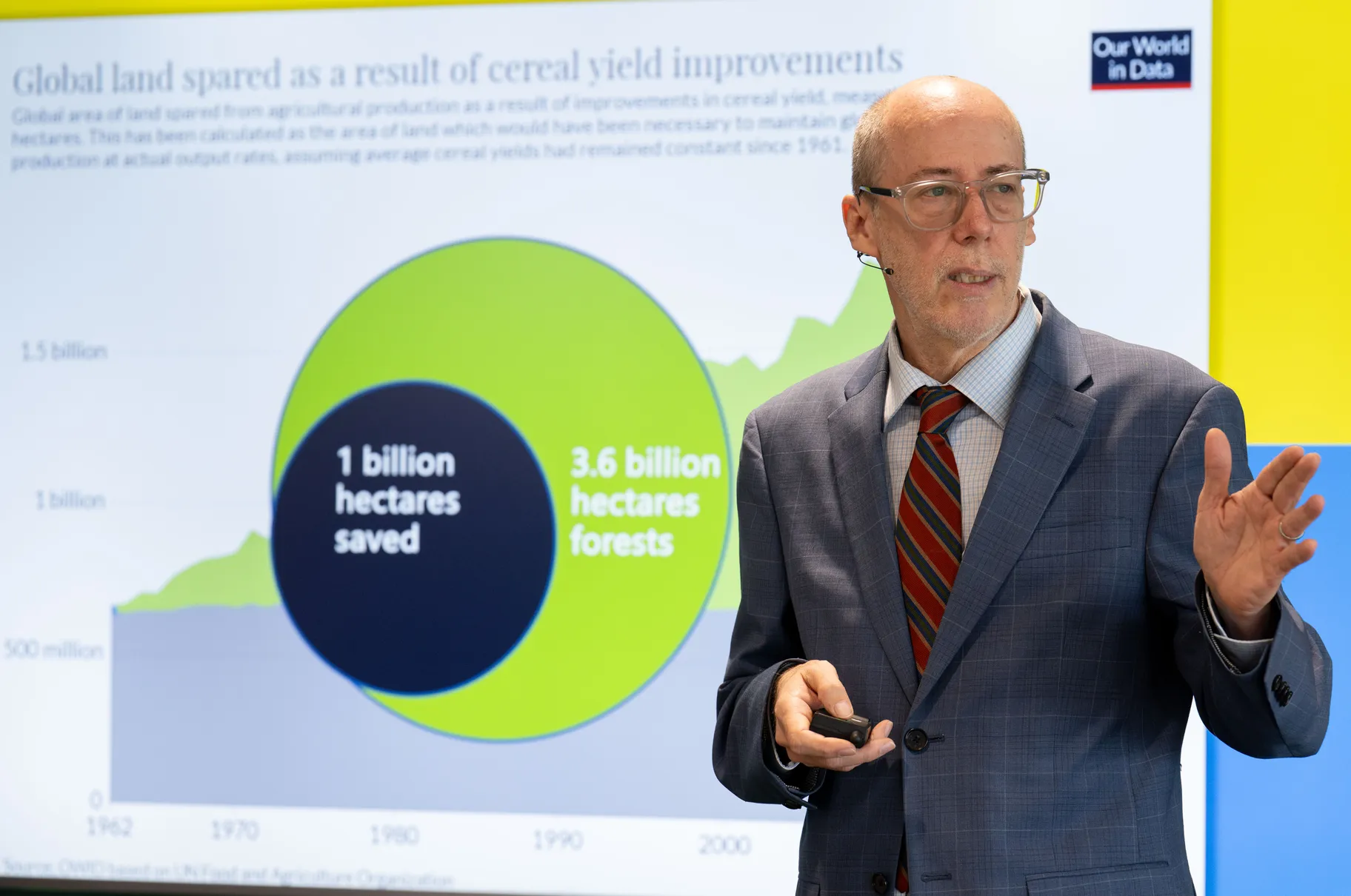

“We were shocked when almost 1,000 people showed up to see Chef Adrià’s lecture,” Rowat said. “Chef Adrià was excited to develop a collaboration with Harvard, so my colleagues and I put together the first ‘science & cooking’ class, which introduced concepts in soft matter physics to undergraduates. Each week, we presented a different scientific concept — think foams and emulsions — and a top chef flew in to do a demo.”

When Rowat joined the UCLA faculty in 2011, she created a class with a similar format, “science & food,” with scientific concepts presented each week that align with real-life examples of food and cooking. Before COVID, the class even included an apple pie bake-off, where students applied the scientific concepts they learned in class to bake the perfect pie (as featured in this New York Times piece).

This kind of creative thinking, alongside her work in cancer research and in the field of cellular agriculture, are just some of the reasons Rowat was chosen to receive the 2025 Gold Shield Faculty Prize, sponsored by Gold Shield, Alumnae of UCLA. One of UCLA’s oldest affinity organizations, Gold Shield has been awarding the faculty prize since 1986 to mid-career faculty with extraordinary accomplishments in teaching, research and service. The prize comes with an unrestricted $30,000 award.

Researchers in Rowat’s lab are pioneering next-generation mechanotyping technologies that are reshaping how we understand — and treat — cancer. By identifying compounds that make cancer cells stiffer and less able to invade surrounding tissue, their work opens new therapeutic avenues aimed at blocking metastasis and making cancer treatments more effective and less toxic for patients.

And while cancer remains a central focus, the lab applies similar principles to engineer tissues that can nourish people sustainably; a major goal of this emerging field of cellular agriculture is to supplement conventional meat production to feed the world’s growing population. Rowat’s research offers a powerful platform to advance human health — demonstrating how fundamental science can drive transformative change across industries from cancer clinics to food security.

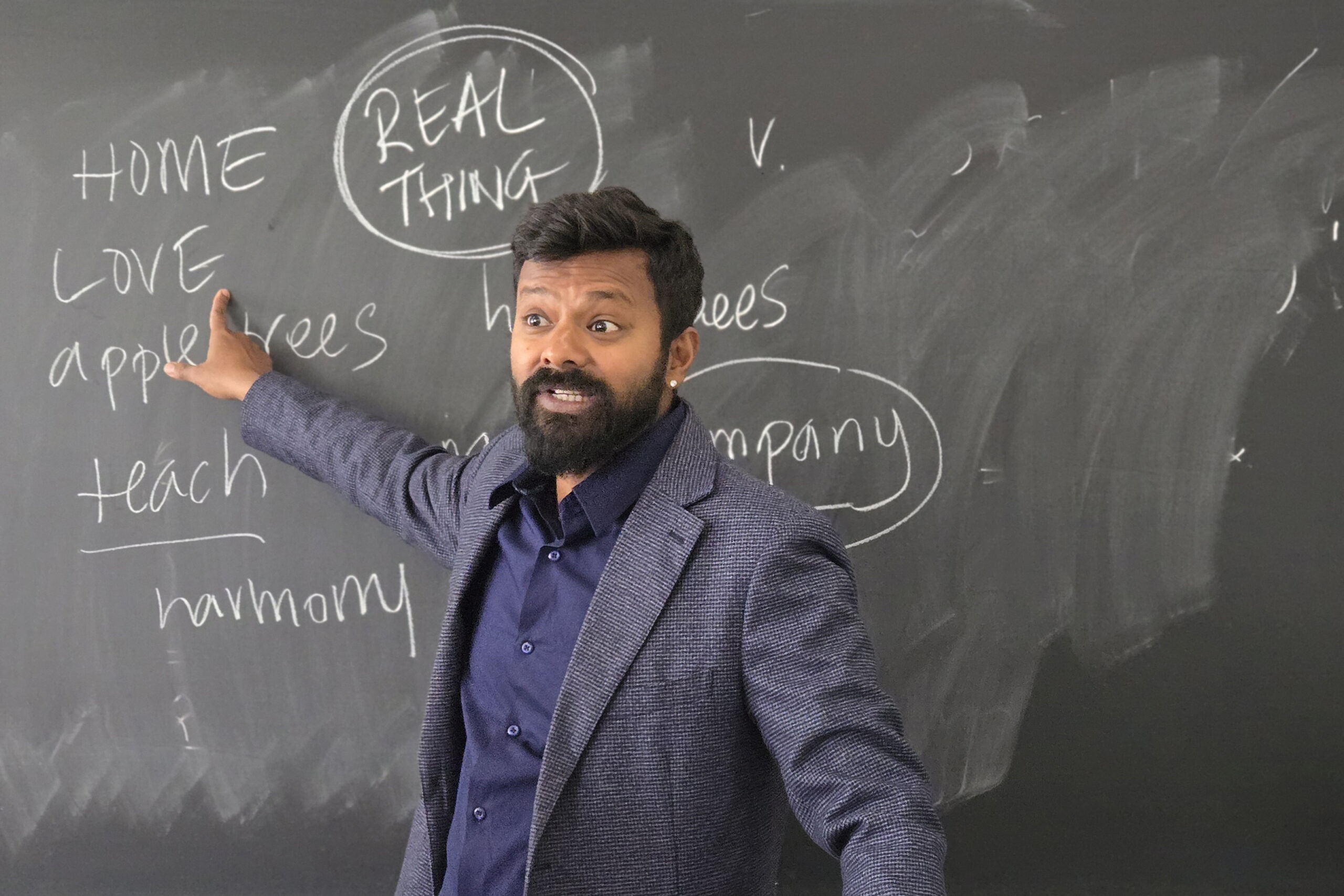

Students in Rowat’s food studies and physiological sciences courses, meanwhile, have been thoroughly inspired by her teaching. An undergraduate in one of her classes praised the biophysicist’s teaching style. “The materials required help us to know the material more in-depth, and we are provided with the direct correlations between what we learn on paper and what we see in the world,” the student said. “Professor Rowat does a wonderful job of bridging the gap between numbers and meaning, science and life.”

Rachelle Crosbie, professor and chair of the department of integrative biology & physiology, emphasized how perfectly Rowat, who is also a member of the UCLA bioengineering department, the Center for Biological Physics, the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Broad Stem Cell Research Center, matched all the criteria for the Gold Shield Faculty Prize. In her nomination letter, she described how Rowat uses food to transform the public’s understanding and appreciation of inquiry-based research, and how her tremendous accomplishments in education are driven by her motivation to reach and teach the next generation.

“Professor Rowat’s research program in mechanobiology continues to be funded by competitive national and international awards and grants,” Crosbie added. “Her accomplishments to create and develop innovative curricula, including the ‘science & food’ public lecture programs and K-12 curricular resources, are borne out of her dedication to increase accessibility of science careers to all.”

Besides being founder and director of Science & Food — a UCLA organization that promotes knowledge of science through food — Rowat holds the Marcie H. Rothman Presidential Chair in Food Studies and is an Allen Distinguished Investigator. She also serves as vice chair of graduate education in the department of integrative biology & physiology; faculty chair of the food studies minor; and faculty director of the Rothman Family Institute for Food Studies.

Born and raised in Guelph, Ontario, Canada, Rowat said she was always drawn to biology but was disappointed to discover that her college classes in the subject were dry and boring. By contrast, her physics professor was extremely engaging and provided the opportunity to solve problems through experiments in the classroom.

“I shifted my focus to physics, but through my training I always sought out projects that applied physics to biology,” she said. “As an undergraduate, I designed capacitive sensors to measure the forces I exerted while running; as a graduate student, I was captivated by understanding why blood cells have special material properties that allow them to deform through narrow gaps to circulate throughout the body, and a particular shape that enables them to maximize the exchange of gases. This link between cell shape, form and function is a theme that still fascinates me and inspires our lab’s research.”

“What set professor Rowat apart was the rare combination of creativity, academic rigor and meaningful impact across teaching, research and service,” said Michellene DeBonis, chair of the Gold Shield Faculty Prize Committee. “She has a gift for making complex science approachable — using food as a lens to explore biophysics in ways that are both intellectually rich and deeply engaging for students. Combined with her groundbreaking interdisciplinary research and her commitment to building community at UCLA, she truly embodies what this prize is meant to honor.”

Rowat is excited and grateful for the $30,000 in prize money, which she says will support her lab’s research on cancer cell mechanobiology. “Using a new platform we developed based on tumor cell deformability, we recently discovered new targets to block cancer spread. The Gold Shield award will allow us to advance mechanotherapeutics with the ultimate goal of better controlling cancer,” she said.